LaTeX et phonologie

Dernière mise à jour : March 04, 2024

Contenu

Transcription phonétique (API)

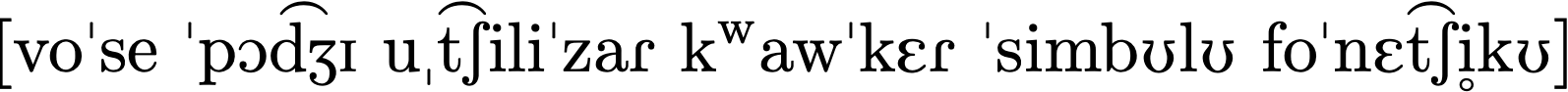

Tout ce dont on a besoin pour produire les symboles phonétiques de l’alphabet phonétique international avec \(\LaTeX\) est l’extension tipa. Vous pouvez consulter son tableau de fonctions ici. Voici un exemple du portugais :

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage{tipa} %

\newcommand{\ipa}{\textipa}

\begin{document}

\ipa{[vo"se "pO\t{dZ}I u""\t{tS}ili"zaR k\super

waw"kER "simbUlU fo"nE\t{tS}\r*ikU]}

% "You can use any phonetic symbol"

\end{document}- Consultez aussi la fonction

ipa2tipa()dans l’extensionFonologyici.

Extras

Voici quelques symboles spécifiques qui ne sont pas trouvés dans le tableau de fonctions mentionné ci-dessus.

- /l/ vélarisé :

\textltilde - Schwa rhoticisé :

\textrhookschwa - Voyelle mi-ouverte centrale non arrondie rhoticisée :

\textrhookrevepsilon

L’extension tipa peut ne pas fonctionner de manière optimale si vous envisagez d’utiliser une police différente.

Voyelles

Vous pouvez utiliser l’extension vowel(voyez ici). Voici un exemple avec toutes les voyelles (de cette façon, vous pouvez simplement masquer les lignes des voyelles dont vous n’avez pas besoin).

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage{tipa,vowel}

\begin{document}

\begin{center}

{\Large

\begin{vowel}

\putcvowel[l]{i}{1}

\putvowel[l]{i}{0pt}{0pt}

\putcvowel[r]{y}{1}

\putcvowel[l]{e}{2}

\putcvowel[r]{\textipa{\o}}{2}

\putcvowel[l]{\textipa{E}}{3}

\putcvowel[r]{\textipa{\oe}}{3}

\putcvowel[l]{\textipa{a}}{4}

\putcvowel[r]{\textscoelig}{4}

\putcvowel[l]{\textipa{A}}{5}

\putcvowel[r]{\textipa{6}}{5}

\putcvowel[l]{\textipa{2}}{6}

\putcvowel[r]{\textipa{O}}{6}

\putcvowel[l]{\textipa{7}}{7}

\putcvowel[r]{\textipa{o}}{7}

\putcvowel[l]{\textipa{W}}{8}

\putcvowel[r]{\textipa{u}}{8}

\putcvowel[l]{\textipa{1}}{9}

\putcvowel[r]{\textipa{0}}{9}

\putcvowel[l]{\textipa{9}}{10}

\putcvowel[r]{\textipa{8}}{10}

\putcvowel{\textipa{@}}{11}

\putcvowel[l]{\textipa{3}}{12}

\putcvowel[r]{\textcloserevepsilon}{12}

\putcvowel{\textipa{I}\ \textipa{Y}}{13}

\putcvowel{\textipa{U}}{14}

\putcvowel{\textipa{5}}{15}

\putcvowel{\textipa{\ae}}{16}

\end{vowel}

}

\end{center}

\end{document}Diagramme vocalique en 3D

Voici un diagramme adapté de Ladefoged & Maddieson (1996, p. 283). Contrairement à la figure ci-dessus, ce diagramme n’est pas créé avec l’extension vowel. À la place, on utilise tikz et des fonctions telles que \path pour ajouter les nœuds, et \draw pour les connecter — voyez les exemples ci-dessous.

Arbres prosodiques

Il y a plusieurs façons de dessiner des structures non linéaires avec \(\LaTeX\). La façon la plus facile est probablement de les émuler avec les arbres syntactiques traditionnels (e.g., l’extension qtree). Toutefois, cette extension crée des branches symétriques par défaut. Voici deux façons de le faire asymétriquement.

Exemple 1

Peut-être la solution la plus connue, tikz est une extension puissante de \(\LaTeX\) qui nous aide à dessiner des structures non linéaires. D’abord, on détermine où exactement on veut dessiner un nœud et voilà. Le code semble désordonné, mais cela changera à mesure que vous vous familiariserez avec la syntaxe de tikz.

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage{textgreek}

\usepackage{tikz}

\usepackage{pgf}

\usetikzlibrary{backgrounds, matrix, positioning}

\usepackage{tipa}

\begin{document}

\begin{tikzpicture}

%

\draw[solid] (4,1.95) node[above](wd2){\textomega} -- (0,1.24);

\draw[solid] (4,1.95) -- (2,1.24);

\draw[solid] (4,1.95) -- (4,1.24);

%

\foreach \x in {0,2,4}

\draw[solid] (\x,0.75) node[above](foot){\textSigma} --

(\x,0) node[below](head){\textsigma};

%

\draw[solid] (0,0.75) -- (1,0) node[below](dep){\textsigma};

\draw[solid] (2,0.75) -- (3,0) node[below](dep){\textsigma};

\draw[solid] (4,0.75) -- (5,0) node[below](dep){\textsigma};

%

\node[draw=none, below] at (0,-0.3) {\strut a};

\node[draw=none, below] at (1,-0.3) {\strut pa};

\node[draw=none, below] at (2,-0.3) {\strut la};

\node[draw=none, below] at (3,-0.3) {\strut chi};

\node[draw=none, below] at (4,-0.3) {\strut co};

\node[draw=none, below] at (5,-0.3) {\strut la};

%

\end{tikzpicture}

\end{document}Exemple 2

Voici un exemple pour le mot blend en anglais qui combine une syllabe typique et ses phonèmes — leur sonorité montrée avec différentes hauteurs (consultez le logiciel ici).

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage{tikz}

\usepackage{tipa}

\begin{document}

\begin{tikzpicture}[scale = 0.8]

\path (2,5.5) node(sigma) {\strut \textsigma};

\path (0.5,2.5) node(O) {\strut O};

\path (2,4) node(R) {\strut R};

\path (2,2.55) node(N) {\strut N};

\path (3.5,2) node(C) {\strut C};

%

\node at (0,0) [circle, draw, inner sep = 0pt] (b) {\strut \textipa{b}};

\node at (1,0.8) [circle, draw, inner sep = 0pt] (l) {\strut \textipa{l}};

\node at (2,1.5) [circle, draw, inner sep = 0pt] (e) {\strut \textipa{E}};

\node at (3,0.6) [circle, draw, inner sep = 0pt] (n) {\strut \textipa{n}};

\node at (4,0) [circle, draw, inner sep = 0pt] (d) {\strut \textipa{d}};

\node at (2,-1) (caption) {`blend'};

%

\draw[dashed] (b) -- (l) -- (e) -- (n) -- (d);

\draw (sigma.south) -- (O.north);

\draw (O.south) -- (b.north);

\draw (O.south) -- (l.north);

\draw (sigma.south) -- (R.north);

\draw (R.south) -- (N.north);

\draw (R.south) -- (C.north);

\draw (N.south) -- (e.north);

\draw (C.south) -- (n.north);

\draw (C.south) -- (d.north);

\end{tikzpicture}

\end{document}Exemple 3

Une alternative à tikz implique l’utilisation d’un tableau comme un modèle pour la représentation. Si l’on dessinait la structure prosodique sur une grille, on pourrait faire référence à une cellule spécifique pour localiser des nœuds (similaire à l’exemple 2 ci-dessus). Voici un exemple simple (nasalisation en anglais).

\usepackage{textgreek}

\usepackage{tikz}

\usepackage{pgf}

\usetikzlibrary{backgrounds, matrix, positioning}

\usepackage{tipa}

...

\begin{tikzpicture}

\matrix [matrix of nodes, row sep=1em,

column sep={2.5em,between origins},

row 5/.style={font=\scshape}]

%

{

& & |(top)| {\textsigma} && \\

|(onset)| O & & |(rhyme)| R && \\

& & |(nucleus)| N && |(coda)| C \\

& & |(mora1)| {$\mu$} && |(mora2)| {$\mu$} \\

|(r1)| rt & & |(r2)| rt && |(r4)| rt \\

|(c1)| C & & |(v1)| V && |(c2)| C \\

|(k)| /k/ & & |(a)| /{\textipa{\ae}}/ && |(n)| /{\textipa{n}}/ \\[1.5em]

& & && |(nf)| [nas] \\

};

%

% Top links (from syllable)

\draw foreach \x in {onset, rhyme} {(top.south) -- (\x.north)};

\draw foreach \x in {nucleus, coda} {(rhyme.south) -- (\x.north)};

%

% Linking onset, nucleus, and coda

\draw (onset.south) -- (r1.north);

\draw (nucleus.south) -- (mora1.north);

\draw (coda.south) -- (mora2.north);

%

\draw (mora1.south) -- (r2.north);

\draw (mora2.south) -- (r4.north);

%

\draw (r1.south) -- (c1.north);

\draw (r2.south) -- (v1.north);

\draw (r4.south) -- (c2.north);

\draw (c1.south) -- (k.north);

\draw (v1.south) -- (a.north);

\draw (c2.south) -- (n.north);

\draw (n.south) -- (nf.north);

\draw[dashed] (a.south) -- (nf.north);

%

\end{tikzpicture} Géométrie des traits

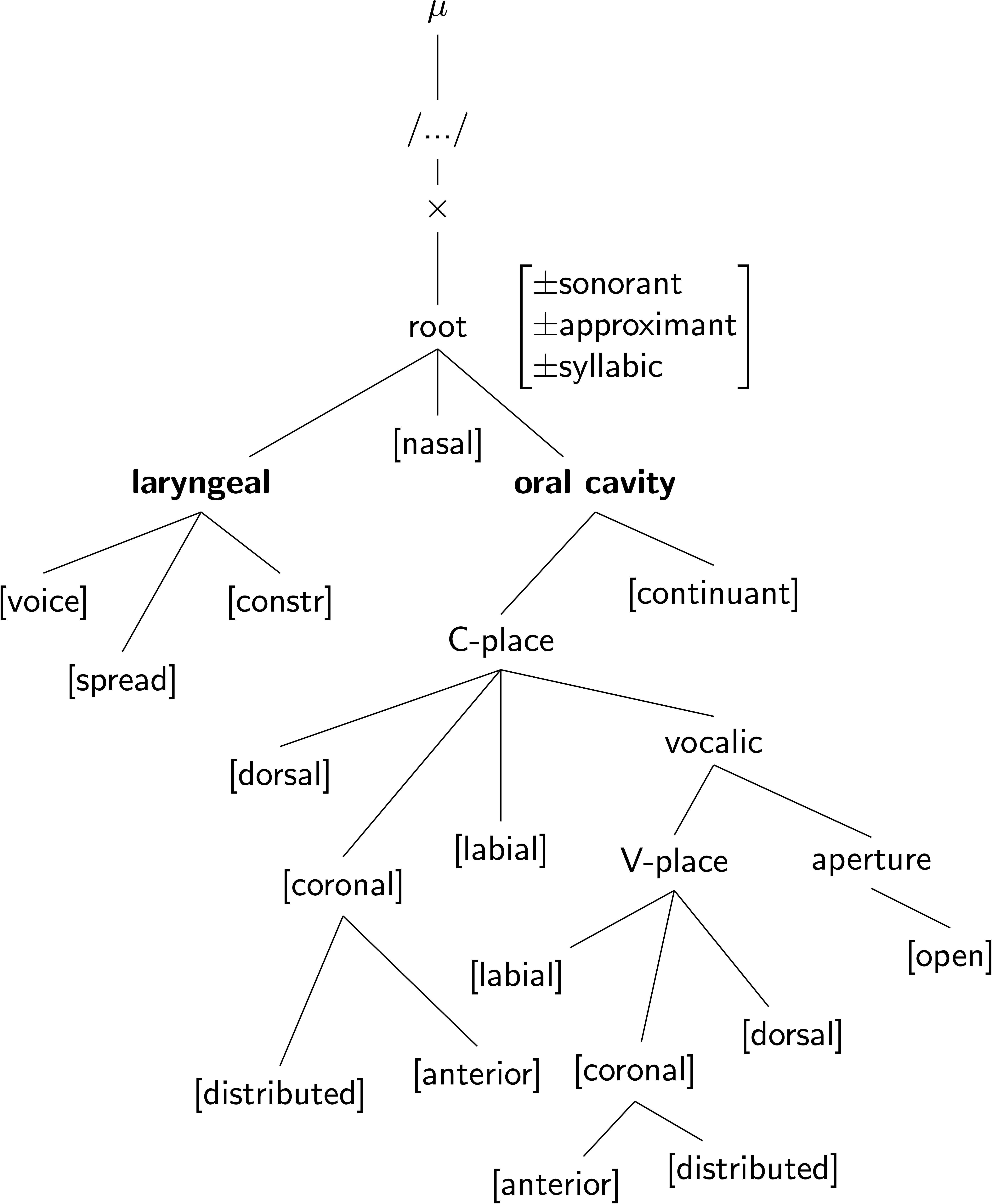

Représentation générale

Une fois que vous êtes habitué à tikz, c’est facile de dessiner n’importe quelles structures non linéaires. La géométrie des traits est essentiellement la même chose, mais plus sophistiquée à la surface. L’arbre ci-dessous est adapté de Clements & Hume (1995, p. 292).

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage{mathtools}

\usepackage{tikz}

\usepackage{pgf}

\usetikzlibrary{backgrounds, matrix, positioning}

\usepackage{tipa}

\begin{document}

\textsf{\normalsize

%

\begin{tikzpicture}[scale = 0.8]

%

%

%

%

%

\path (4,13) node (mora) {{$\mu$}};

\path (4,11.5) node (seg) {{/.../}};

\path (4,10.5) node (x) {{$\times$}};

\path (4,9) node (root) {{root}};

%

% Matrix by root node:

\path (6.5,9) node (matrix) {$\begin{bmatrix*}[l]\pm

\text{sonorant}\\

\pm \text{approximant}\\

\pm \text{syllabic}\end{bmatrix*}$};

%

%

\path (1,7) node (lar) {\textbf{laryngeal}};

\path (-1,5.5) node (vce) {{[voice]}};

\path (0,4.5) node (sg) {{[spread]}};

\path (2,5.5) node (cg) {{[constr]}};

%

\path (6,7) node (oral) {\textbf{oral cavity}};

\path (4,7.5) node (nasal) {{[nasal]}};

%

%

\path (7.5,5.6) node (cont) {{[continuant]}};

%

\path (4.8,5) node (Cplace) {{C-place}};

\path (2,3.3) node (dor) {{[dorsal]}};

\path (2.8,1.9) node (cor) {{[coronal]}};

\path (4.5,-0.5) node (ant) {{[anterior]}};

\path (2,-0.75) node (distr) {{[distributed]}};

\path (4.8,2.35) node (lab) {{[labial]}};

%

\path (7.5, 3.75) node (vocalic) {vocalic};

\path (7, 2.2) node (Vplace) {V-place};

\path (5, 0.75) node (Vlab) {[labial]};

\path (6.5, -0.45) node (Vcor) {[coronal]};

\path (5.5, -1.9) node (Vant) {[anterior]};

\path (8, -1.7) node (Vdistr) {[distributed]};

\path (8.5, 0) node (Vdor) {[dorsal]};

%

\path (9.5, 2.2) node (aperture) {aperture};

\path (10.5, 1.0) node (open) {[open]};

%

%

\draw (seg.north) -- (mora.south);

\draw (x.north) -- (seg.south);

\draw (root.north) -- (x.south);

\draw (root.south) -- (lar);

\draw (root.south) -- (oral);

\draw (root.south) -- (nasal.north);

\draw (oral.south) -- (cont.north);

\draw (lar.south) -- (vce.north);

\draw (lar.south) -- (sg.north);

\draw (lar.south) -- (cg.north);

%

\draw (oral.south) -- (Cplace.north);

%

\draw (Cplace.south) -- (dor.north);

\draw (Cplace.south) -- (cor.north);

\draw (Cplace.south) -- (lab.north);

\draw (cor.south) -- (distr.north);

\draw (cor.south) -- (ant.north);

%

\draw (Cplace.south) -- (vocalic.north);

\draw (vocalic.south) -- (Vplace.north);

\draw (vocalic.south) -- (aperture.north);

\draw (open.north) -- (aperture.south);

\draw (Vplace.south) -- (Vlab);

\draw (Vplace.south) -- (Vdor);

\draw (Vplace.south) -- (Vcor);

\draw (Vcor.south) -- (Vant);

\draw (Vcor.south) -- (Vdistr);

%

%

\end{tikzpicture}

}

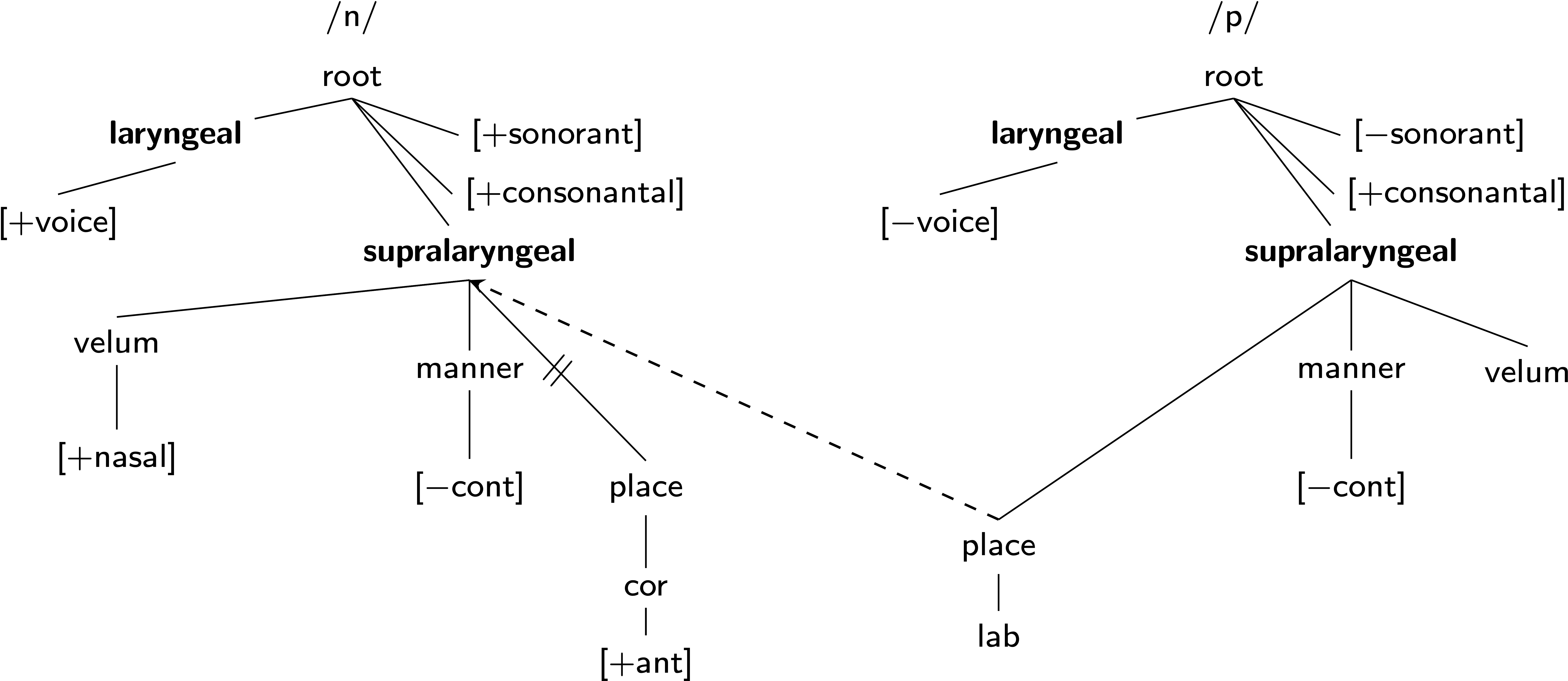

\end{document}Exemple : assimilation nasale

Adapté de Davenport & Hannahs (2020, p. 162).

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage{mathtools}

\usepackage{tikz}

\usepackage{pgf}

\usetikzlibrary{backgrounds, matrix, positioning}

\usepackage{tipa}

\begin{document}

{\footnotesize\textsf{

%

\begin{tikzpicture}[scale = 0.5]

%

\path (4,8) node (n) {\footnotesize\textipa{/n/}};

\path (4,7) node (root) {{root}};

\path (1,6) node (lar) {\textbf{laryngeal}};

\path (-1,4.5) node (vce) {{[$+$voice]}};

\path (6,4) node (supra) {\textbf{supralaryngeal}};

\path (7.5,6) node (son) {{[$+$sonorant]}};

\path (7.8,5) node (cons) {{[$+$consonantal]}};

\path (0,2.5) node (velum) {{velum}};

\path (0,0.5) node (nasal) {{[$+$nasal]}};

\path (6,2) node (manner) {{manner}};

\path (6,0) node (cont) {{[$-$cont]}};

\path (9,0) node (place) {{place}};

\path (9,-1.7) node (cor) {{cor}};

\path (9,-3) node (ant) {{[$+$ant]}};

\draw (root.south) -- (lar) ;

\draw (root.south) -- (supra) ;

\draw (supra.south) -- (velum.north);

\draw (root.south) -- (son.west);

\draw (root.south) -- (cons.west);

\draw (velum.south) -- (nasal.north);

\draw (supra.south) -- (manner.north);

\draw (manner.south) -- (cont.north);

\draw (lar.south) -- (vce.north);

\draw (supra.south) -- node[circle,

midway,

rotate = -40]{

\textbf{$||$}}(place.north);

\draw (place.south) -- (cor.north);

\draw (cor.south) -- (ant.north);

%

% Second tree

%

\begin{scope}[xshift = 15cm, yshift = 0cm, scale=1]

%

\path (4,8) node (p) {\footnotesize\textipa{/p/}};

\path (4,7) node (root) {{root}};

\path (1,6) node (lar) {\textbf{laryngeal}};

\path (-1,4.5) node (vce) {{[$-$voice]}};

\path (6,4) node (supra2) {\textbf{supralaryngeal}};

\path (7.5,6) node (son) {{[$-$sonorant]}};

\path (7.8,5) node (cons) {{[$+$consonantal]}};

\path (9,2) node (velum) {{velum}};

\path (6,2) node (manner) {{manner}};

\path (6,0) node (cont) {{[$-$cont]}};

\path (0,-1) node (place2) {{place}};

\path (0,-2.5) node (lab) {{lab}};

%

\draw (root.south) -- (lar) ;

\draw (root.south) -- (supra2) ;

\draw (supra2.south) -- (velum.north);

\draw (root.south) -- (son.west);

\draw (root.south) -- (cons.west);

\draw (supra2.south) -- (manner.north);

\draw (manner.south) -- (cont.north);

\draw (lar.south) -- (vce.north);

\draw (supra2.south) -- (place2.north);

\draw (place2.south) -- (lab.north);

\draw (cor.south) -- (ant.north);

%

\draw[-stealth, dashed, semithick] (place2.north) --

(supra.south);

\end{scope}

\end{tikzpicture}

}}

\end{document}Prosodie + géométrie des traits

L’extension tikz nous donne beaucoup de flexibilité. Par exemple, on peut créer un arbre qui combine la hiérarchie prosodique en utilisant la fonction Tree et, en même temps, la géométrie des traits en utilisant la fonction path. Vous pouvez créer des nœuds entre les deux objets (environnement) avec la fonction scope. Voici un exemple simplifié pour pretty butterfly en anglais.

L’interface entre la phonologie et lamorphologie

Les représentations ci-dessous sont adaptées à partir de Booij (2012, p. 159).

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage[LGRgreek]{mathastext}

\usepackage{tikz}

\begin{document}

{\scriptsize

\begin{tikzpicture}[scale = 0.9]

%

% MORPHOLOGGY FOR INTERNATIONAL

%

\path (1.5,1) node (pr) {\strut{Af}};

\path (3.5,1) node (n) {\strut{N}};

\path (4.25,2) node (adj1) {\strut{Adj}};

\path (4.25,3) node (adj2) {\strut{Adj}};

\path (5,1) node (su) {\strut{Af}};

\path (1,0) node (in) {\strut{\textbf{in}}};

\path (2,0) node (ter) {\strut{\textbf{ter}}};

\path (3,0) node (na) {\strut{\textbf{na}}};

\path (4,0) node (tion) {\strut{\textbf{tion}}};

\path (5,0) node (al) {\strut{\textbf{al}}};

%

% PHONOLOGY FOR INTERNATIONAL

%

\path (1,-1) node (s1) {\strut{$\sigma$}};

\path (2,-1) node (s2) {\strut{$\sigma$}};

\path (3,-1) node (s3) {\strut{$\sigma$}};

\path (4,-1) node (s4) {\strut{$\sigma$}};

\path (5,-1) node (s5) {\strut{$\sigma$}};

\path (1,-2) node (f1) {\strut{$\Sigma$}};

\path (3,-2) node (f2) {\strut{$\Sigma$}};

\path (3,-3) node (w) {\strut{$\omega$}};

%

% LINES

%

\draw (in.north) -- (pr.south);

\draw (ter.north) -- (pr.south);

\draw (na.north) -- (n.south);

\draw (tion.north) -- (n.south);

\draw (al.north) -- (su.south);

\draw (su.north) -- (adj1.south);

\draw (al.south) -- (s5.north);

\draw (n.north) -- (adj1.south);

\draw (adj1.north) -- (adj2.south);

\draw (pr.north) -- (adj2.south);

\draw (in.south) -- (s1.north);

\draw (ter.south) -- (s2.north);

\draw (na.south) -- (s3.north);

\draw (tion.south) -- (s4.north);

\draw (s1.south) -- (f1.north);

\draw (s2.south) -- (f1.north);

\draw (s3.south) -- (f2.north);

\draw (s4.south) -- (f2.north);

\draw (s5.south) -- (w.north);

\draw (f1.south) -- (w.north);

\draw (f2.south) -- (w.north);

\draw (2.7,-0.2) rectangle (4.4,0.2);

\path (4.4, -0.33) node (stem) {\tiny \emph{stem}};

%

\end{tikzpicture}

%

\hspace{4em}

%

\begin{tikzpicture}[scale = 0.9]

%

% MORPHOLOGGY FOR NEIGHBORHOOD

%

\path (1.5,1) node (n1) {\strut{N}};

\path (1.5,3) node (n2) {\strut{N}};

\path (3,1) node (af) {\strut{Af}};

\path (1,0) node (neigh) {\strut{\textbf{neigh}}};

\path (2,0) node (bor) {\strut{\textbf{bor}}};

\path (3,0) node (hood) {\strut{\textbf{hood}}};

%

% PHONOLOGY FOR NEIGHBORHOOD

%

\path (1,-1) node (s1) {\strut{$\sigma$}};

\path (2,-1) node (s2) {\strut{$\sigma$}};

\path (3,-1) node (s3) {\strut{$\sigma$}};

\path (1,-2) node (f1) {\strut{$\Sigma$}};

\path (3,-2) node (f2) {\strut{$\Sigma$}};

\path (1,-3) node (w) {\strut{$\omega$}};

%

% LINES

%

\draw (neigh.north) -- (n1.south);

\draw (bor.north) -- (n1.south);

\draw (hood.north) -- (af.south);

\draw (af.north) -- (n2.south);

\draw (n1.north) -- (n2.south);

\draw (neigh.south) -- (s1.north);

\draw (bor.south) -- (s2.north);

\draw (hood.south) -- (s3.north);

\draw (s1.south) -- (f1.north);

\draw (s2.south) -- (f1.north);

\draw (s3.south) -- (f2.north);

\draw (f1.south) -- (w.north);

\draw (f2.south) -- (w.north);

\draw (0.5,-0.2) rectangle (2.35,0.2);

\path (2.35, -0.33) node (stem) {\tiny \emph{stem}};

%

\end{tikzpicture}

}

\end{document}Règles SPE (The Sound Pattern of English)

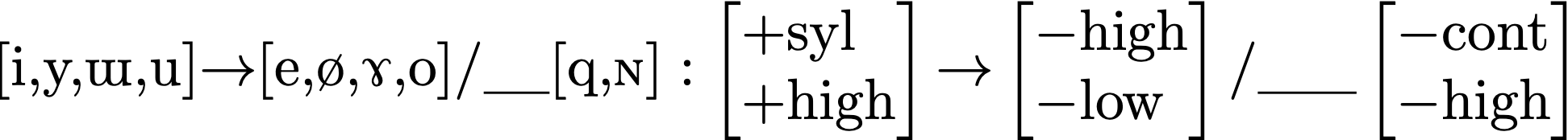

Pour les règles SPE (Chomsky & Halle, 1968), on a besoin de matrices. Par conséquent, vous pouvez lire sur ce sujet et transférer les aspects fondamentaux. Ici, on peut utiliser l’extension mathtools. J’utilise la fonction \text{} pour ne pas avoir les traits en italique. Le [l] à côté de \begin{bmatrix*} spécifie l’alignement des traits dans la matrice. L’exemple ci-dessous est d’une langue hypothétique où les voyelles hautes s’abaissent si suivies de consonnes uvulaires.

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage{amsmath}

\usepackage{mathtools}

\usepackage{mathabx}

\usepackage{MnSymbol}

\usepackage{tipa}

\begin{document}

\[

\text{\textipa{[i,y,W,u]}} {\rightarrow} \text{\textipa{[e,\o,7,o]}}/{

\underline{\hspace{0.4cm}}} \text{\textipa{[q,\;N]}}:

%

\begin{bmatrix*}[l]

+\text{syl}\\

+\text{high}

\end{bmatrix*}

%

{\rightarrow}

%

\begin{bmatrix*}[l]

-\text{high}\\

-\text{low}

\end{bmatrix*}

/

\underline{\hspace{0.6cm}}

%

\begin{bmatrix*}[l]

-\text{cont}\\

-\text{high}

\end{bmatrix*}

\]

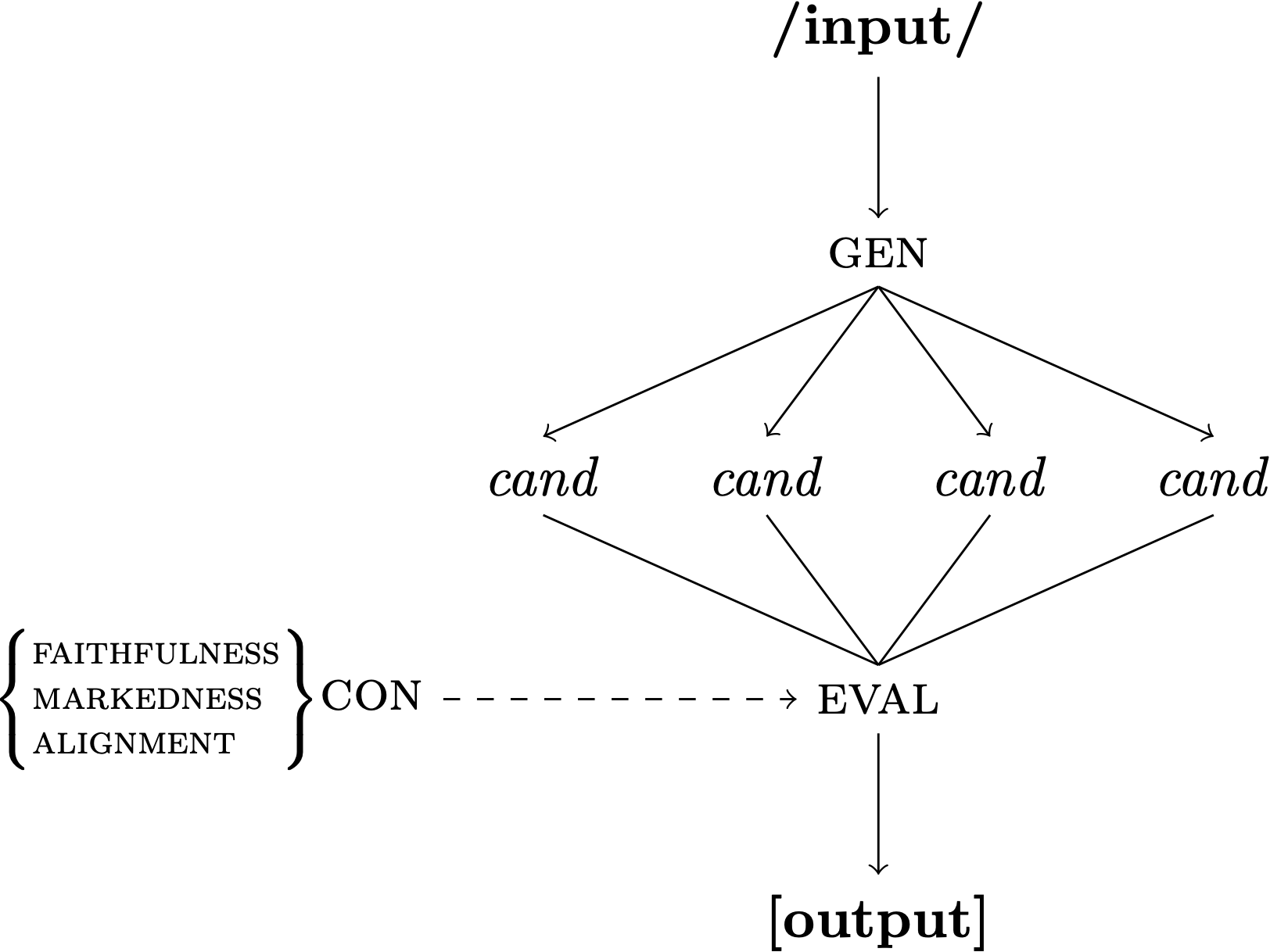

\end{document}L’architecture de la théorie de l’optimalité

Après avoir compris les structures non linéaires ci-dessus, c’est facile de dessiner l’architecture typique de la TO (Prince & Smolensky, 1993). J’utilise tikz ici de nouveau.

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage{amsmath}

\usepackage{mathtools}

\usepackage{mathabx}

\usepackage{MnSymbol}

\usepackage{tipa, tikz}

\begin{document}

%

\begin{tikzpicture}[scale = 1.4]

\path (0,5) node(input) {\textrm{\textbf{/input/}}};

\path (0,4) node(gen) {\textsc{gen}};

\foreach \x in {1,...,4} {

\path (\x-2.5, 3) node(cand\x) {\textrm{\emph{cand}}};

}

%

\path(0,2) node(eval) {\textsc{eval}};

\path(0,1) node(output) {\textrm{\textbf{[output]}}};

%

\path(-3,2) node(con) {\scriptsize$\begin{Bmatrix*}[l]

\text{\textsc{faithfulness}}\\

\text{\textsc{markedness}}\\

\text{\textsc{alignment}}

\end{Bmatrix*}$\textsc{con}};

%

%

\draw[->] (input) -- (gen);

\foreach \x in {1,...,4} {

%

\draw[->] (gen.south) -- (cand\x.north);

\draw[] (cand\x.south) -- (eval.north);

}

%

\draw[->, dashed] (con) -- (eval);

\draw[->] (eval) -- (output);

%

\end{tikzpicture}

%

\end{document} Copyright © Guilherme Duarte Garcia